Otago landscape

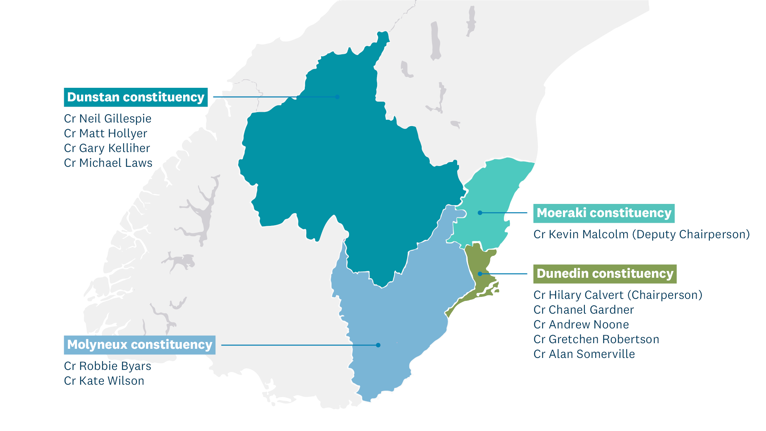

Otago Regional Councillors represent the region's four constituencies — Dunedin, Moeraki, Dunstan, and Molyneux.

Your elected Otago Regional Councillors represent the region's four constituencies — Dunedin, Dunstan, Moeraki and Molyneux.

Back row left to right: Cr Matt Hollyer, Dunstan; Cr Andrew Noone, Dunedin; Cr Neil Gillespie, Dunstan; Cr Alan Somerville Dunedin; Cr Gary Kelliher, Dunstan; Cr Kate Wilson, Molyneux

Front row left to right: Cr Gretchen Robertson, Dunedin; Deputy Chairperson Kevin Malcolm, Moeraki; Chairperson Hilary Calvert, Dunedin; Cr Chanel Gardner, Dunedin; Cr Robbie Byars, Molyneux

Inset: Cr Michael Laws, Dunstan

There are five councillors who represent the Dunedin constituency. Dunedin is comprised of central Dunedin and the Waikouaiti Coast, West Harbour, Otago Peninsula and Saddle Hill community board areas located within the Dunedin City territorial area.

Chairperson - Dunedin Constituency | Portfolio lead for Strategy and Customer

Councillor - Dunedin Constituency | Portfolio lead for Finance

Councillor - Dunedin Constituency | Portfolio lead for Environmental Delivery

Councillor - Dunedin Constituency | Portfolio lead for Science and Resilience

Councillor - Dunedin Constituency | Portfolio lead for Transport

There are two councillors who represent the Molyneux constituency. Molyneux is comprised of the Clutha District territorial area and the Mosgiel-Taieri and Strath-Taieri community board areas located within the Dunedin City territorial area.

There are four councillors who represent the Dunstan constituency. Dunstan is comprised of the Central Otago District and Queenstown Lakes District territorial areas.

Councillor - Dunstan Constituency | Portfolio lead for Policy and Planning

Councillor - Dunstan Constituency | Portfolio lead for Transport

Councillor - Dunstan Constituency | Portfolio lead for Science and Resilience

Councillor - Dunstan Constituency | Portfolio lead for Strategy and Customer

There is one councillor who represents the Moeraki constituency. Moeraki is comprised of the Otago portion of Waitaki District territorial area, being part of the Ahuriri and Corriedale wards, and the entirety of the Oamaru and Waihemo wards.