The Alpine Fault runs along the line where the tectonic plates under the South Island meet – it connects two “subduction” margins where the ocean floor descends into the Earth’s mantle.

The eastern Pacific Plate is moving westwards, and the western Australian Plate is moving eastwards. They move at a relative rate of about 45mm per year.

The movement of these two plates against each other builds up enormous pressure that must eventually be released through earth movement: a rupture of the Alpine Fault. Between earthquakes, pressure continually builds at this fracture line, and has been building for more than 300 years since it was last released by a large earthquake in 1717 AD.

The Alpine Fault, along with many other active faults, is part of the continuous evolution of the South Island’s mountainous landscape. Our communities must plan to adapt to this hazard and related events such as slips, rivers breaking their banks and liquefaction.

Geologists working on Project AF8 believe that the next severe earthquake on the Alpine Fault is most likely to be a rupture that begins in South Westland and “unzips” northwards. It will probably have a magnitude of 8+ on the Richter Scale and will be felt throughout the South Island and the lower North Island and as far away as Sydney. The map below indicates the range of the earthquake.

The historical patterns of earthquakes and current research on the Alpine Fault indicate that it is likely to rupture very soon in geological terms.

There is a 75% probability of an Alpine Fault earthquake in the next 50 years according to a recent study led by Te Herenga Waka – Victoria University of Wellington senior lecturer Dr Jamie Howarth. Carbon dating has previously confirmed that the last severe earthquake on the Alpine Fault was in 1717, and analysis of lake sediments deposited by previous earthquakes shows that the Central and South Westland sections of the Alpine Fault have ruptured on a remarkably regular basis, about every 250 years. There is also a 4 out of 5 probability that the next Alpine Fault earthquake will involve multiple sections of this faultline, making it a magnitude 8+ event.

Analysis of sediments deposited by previous Alpine Fault earthquakes shows that the faultline ruptures on a remarkably regular basis, on average at intervals around 300 years. Carbon dating confirms that the last severe earthquake on the Alpine Fault was in 1717.

You will find more information about the Alpine Fault, evidence of past earthquakes, and what preparations are being made for a coordinated response across the South Island on the Project AF8 website.

Research from Dr Jamie Howarth

Publications by Dr Jamie Howarth of Victoria University of Wellington - research on the Alpine Fault earthquake.

![AF8 [Alpine Fault Magnitude 8] Logo](/media/gtsgtd2g/af8-logo-1920x1080.png?width=1000&height=560&v=1db77b17f152310)

AF8 [Alpine Fault magnitude 8]

AF8 is an award-winning program that combines scientific modelling, coordinated response planning, and community engagement.

There will be no warning of the earthquake. It may be triggered by the rupture of another faultline nearby, but we will only know this afterwards. The Alpine Fault earthquake will alter tectonic stress distribution, and other faultlines may rupture in the following days or years.

The rupture will be up to 400 km long, e.g. starting on Haast and spreading north to Ahaura. The earthquake will last for about two minutes.

The alpine fault may rupture along part of its length, with lower magnitude, and be followed shortly by rupture of the rest. Two very large earthquakes or a series of large earthquakes are also realistic scenarios.

With an expected magnitude of 8+, this will be considered a “great earthquake” not simply a strong one. In some places, the force will shift the earth sideways by up to eight metres and vertically by about four metres. The effects will be worst in West Otago and lessen towards the east of the island.

Significant building damage can be expected in the Queenstown Lakes District. Damage in other parts of Otago will be irregularly distributed depending on the landforms and the built environment.

If you would like to know more, there is a series of short presentations by scientists who have been researching the Alpine Fault and the impacts of the next rupture, on the EMSouthland YouTube channel.

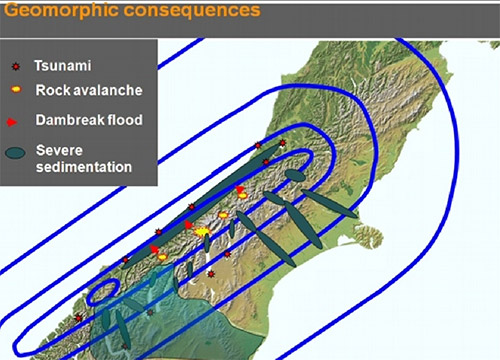

The effects will be amplified in South Island mountainous regions and high country where enormous damage can occur to peaks and ridges. We can expect countless landslides of all sizes. In areas where the magnitude is plus or minus 9, many tens of millions of cubic metres of rock and scree may collapse from slopes.

Damaging aftershocks are likely to continue for several weeks, and the event will have disastrous consequences across many regions. Less intense shaking from aftershocks will continue for months. There will be liquefaction and widespread ground damage.

Landslide dams with breakout flash flooding are highly likely. Large amounts of sediment will be deposited in riverbeds for many months. Huge sediment and gravel deposits will have downstream effects for years. Areas such as the Shotover River may be radically transformed.

Rock avalanches falling into water bodies may cause tsunamis in lakes, rivers and fiords. Areas such as Lakes Wakatipu, Wanaka, Hawea, Te Anau, Manapouri, Tekapo, Milford Sound and Doubtful Sound are at risk from tsunamis induced by massive landslips into the water.

A study released by NIWA in 2018 found evidence of tsunami up to five metres high caused by landslides into Lake Tekapo, which scientists believe will be similar to other large Otago Lakes

A national civil defence emergency of long duration will be called quickly. We can expect that medical services and other civil defence emergency services will be overwhelmed and that the scale of damage to roads and buildings will make rescue efforts extremely difficult. Overseas rescue and medical assistance will be required.

The nature and location of the earthquake relative to major population centres suggest that a relatively small number of people will be killed. However, many people will suffer disabling injuries. Depending on the time of year, the many seasonal visitors in the Queenstown Lakes District and other parts of Otago will be completely reliant on immediate assistance.

We can expect that many bridges will fail west of Queenstown, Wanaka/Hawea as no bridge design performs well during a fault rupture. Many rivers and streams will become impassable. Roads will suffer severe damage and some areas will become isolated immediately. Transalpine routes and roads in mountainous areas will be impassable for weeks, likely stranding tourists and other travellers. Any ski-fields operating at the time of the rupture will face severe rescue difficulties.

In the same way that the 2016 Kaikoura earthquake caused massive landslides to block SH1 for over a year, an Alpine Fault rupture will cut road access through the Kawarau Gorge, Kingston to Frankton, Haast Pass and the Glenorchy Road, mostly due to landslides and dropouts. Large sections of SH6 (Haast Highway) may be out for up to a year. Many other roads will be affected.

Damage to hydro-electrical generation plants and transmission lines will halt South Island power generation and reticulation will face widespread disruption. Electricity supply is likely to be unavailable for many weeks or even months in some remote areas.

The Clyde Dam has been built to very high specifications and it is unlikely it would suffer catastrophic damage.

All communication systems including land and cellphones may be down in many parts of West Otago. Satellite-based telephone systems will initially be the main means of communication. The Wakatipu area, including Queenstown, could become completely isolated if the airport is damaged.

Water, sewerage, energy, transport, health, and social services are likely to be disrupted for weeks.

Most commercial activity may stop in many parts of the South Island, and many local economies will be maintained solely by recovery activities. People trapped on roads and tracks or in accommodation will need to be looked after where they are for days due to road blockages, airport damage, and limited means of transportation.

Agricultural production will be disrupted, and it may not be possible to milk dairy herds in some areas due to electricity outage.

A major problem constraining repair and rebuilding will be the shortage of trades people and materials.

Provision of emergency medical facilities for many major trauma victims and the rescue of trapped people on roads will be severely disrupted for three to four weeks.

Civil Defence Emergency Management Groups across the South Island are working together to plan a coordinated response to the next severe Alpine Fault earthquake. You will find the SAFER Plan for this response on the Project AF8 website.

While the direct impact on people, families and businesses will vary, it is certain that normal life will be disrupted for everyone in the South Island for a long time. Being prepared will make life easier for you and those who rely on you in the aftermath. There is extensive advice on how to be prepared on www.getready.govt.nz and www.otagocdem.govt.nz. Plan to be self-reliant for at least three days – a week or more is realistic. This includes having stored water, food, medical supplies, and alternative means of cooking and heating for your household and your pets.

Look at your home, property or business and develop scenarios about the risk factors. Develop a plan about what you need to be prepared and encourage others to do the same. Check the Emergency Management Otago website to see whether your area has a community response plan. If not, take the initiative and contact Emergency Management Otago to discuss setting up a local community response group.

Email info@otagocdem.govt.nz or phone 0800 474 082.