-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Environment

Community Outcome: Otago has a healthy environment ki uta ki tai (from mountains to the sea), including thriving ecosystems and communities, as well as flourishing biodiversity.

Relevance

Freshwater quality is essential to life in Otago. Clean water supports healthy ecosystems, provides safe drinking water, sustains mahika kai (food and resource gathering), and enables recreation such as swimming, kayaking, and fishing. It also underpins many sectors of Otago’s economy, including tourism, agriculture, and outdoor recreation.

For mana whenua, water is the foundation and source of all life — nā te wai ko te hauora o kā mea katoa. Healthy, clean water is vital for maintaining cultural relationships with waterways and exercising kaitiakitaka (guardianship), ensuring that water sustains both present and future generations.

Freshwater quality is shaped by the interconnectedness of rivers, lakes, wetlands, groundwater, land use, and coastal environments. Healthy wetlands and riparian vegetation help filter sediments and nutrients, regulate water temperature, and support diverse aquatic ecosystems.

Maintaining good water quality requires an integrated approach that recognises what happens on land affects freshwater, and ultimately coastal waters.

Low contaminant levels and stable ecological communities show that a waterway is functioning well. When contaminants such as E. coli, nutrients, sediment, or algae increase beyond natural levels, ecological health declines, habitat becomes less suitable for fish and aquatic invertebrates, and risks to human health rise. Tracking these patterns helps us understand how well our waterways are coping with pressures, where improvements are needed, and where resilience to climate change and extreme events may be vulnerable.

Current situation

Summary

While water quality is still good in Otago’s headwaters and natural catchments, in many parts of the region it is degrading.

Supporting information

Across the region, phosphorus and ammoniacal nitrogen levels are improving, while dissolved inorganic nitrogen, total nitrogen, E. coli, Macroinvertebrate Community Index scores, and clarity are declining.

Mountain and lake-fed rivers show the strongest overall water quality, with more improving trends and fewer signs of decline. In contrast, hill and lowland rivers show the greatest number of degrading trends across key attributes.

In urban areas, industrial catchments have poor and deteriorating water quality, while more natural and residential catchments tend to have better outcomes. While attributing causes to trends is complex, these patterns are consistent with national trends associated with land-use intensification.

How is it measured

For the purpose of this indicator, several indicators have been used to determine whether the health of Otago’s freshwater is improving or deteriorating over the twenty-year period to 2024. In urban Dunedin, available data allows trends to be assessed over the last ten years only.

The indicators used are:

- Biological: Macroinvertebrate Community Index (MCI) — a measure of the community of small stream animals, such as insect larvae, that are sensitive to changes in water quality.

- Chemical:

- Ammonia and nitrate toxicity — nutrients that can make water unsafe for human consumption and harm aquatic life at high levels.

- Dissolved reactive phosphorus (DRP) — a nutrient that can cause excessive plant and algal growth.

- Clarity: A measure affected by fine sediment that can smother habitats and reduce recreational enjoyment.

- Human health risk: Escherichia coli (E. coli) — a bacterium indicating faecal contamination and potential health risks to recreational and drinking water users.

Relevance

A plentiful, reliable supply of freshwater is essential to life in Otago. Water is needed for people and wildlife to drink, to provide habitat for native species and ecosystems, and to support mahika kai (food and resource gathering). Otago’s economy depends on reliable freshwater for agriculture, tourism, hydroelectricity generation, and other industries, and it underpins a wide range of recreation enjoyed by residents and visitors, including swimming, kayaking, and fishing.

For mana whenua, water is the foundation and source of all life — nā te wai ko te hauora o kā mea katoa. Reliable and abundant water is essential for maintaining relationships with waterways and exercising kaitiakitaka (guardianship), ensuring the wellbeing of current and future generations.

Maintaining reliable freshwater is increasingly important for Otago’s resilience to drought and more frequent severe weather events. This requires an integrated approach that recognises the connections between rivers, lakes, wetlands, groundwater, land use, and coastal environments. Healthy wetlands, riparian vegetation, and upland ecosystems play a vital role in storing, filtering, and regulating water, contributing to both ecosystem and community resilience.

In general, when there is plentiful water even under normal levels of use, ecological risk is low. When water takes reduce flows for longer periods than would naturally occur, ecological risk becomes medium to high, as habitat for native fish and aquatic invertebrates is reduced. Understanding these patterns also helps identify where water supply may be unreliable for human use and where future resilience to drought or severe weather may be low.

Current situation

Summary

For most of Otago, there is plenty of water for ecosystems and people. In some areas management still allows ecological impacts and risks water availability.

Supporting information

Across most of Otago, water quantity is being managed well, with sufficient water available to meet current demand while maintaining healthy river flows.

However, several catchments currently experience medium to high ecological risk due to permitted water takes reducing flows for longer periods than would naturally occur. These catchments also have low reliability for human use, meaning water users have less resilience to drought or extreme weather.

Catchments with medium–high ecological risk and low reliability include:

- Manuherekia

- Cardrona

- Kakanui

- Lowburn

- Waianakarua

- Shag

- Luggate

- Waikouaiti

Catchments with low ecological risk and low reliability include:

- Pomahaka

- Mill Creek

- Waiwera

Water quantity in the Clutha/Mata Au is strongly influenced by hydroelectric dam operations, and the Taieri benefits from additional stored water supporting flow reliability.

How is it measured

Freshwater quantity is measured by tracking both natural flow and water use:

- River flow: ORC uses river gauges that record flow daily, providing detailed information on how rivers rise and fall throughout the seasons.

- Water use: Water takes are measured with meters on pumps and pipes, allowing ORC to understand how much water is used for irrigation, town supply, industry, and other activities.

- Ecological risk: These data were combined to assess ecological flow risk in 2024, showing where permitted current water use patterns lead to lower-than-natural flows and elevated ecological stress.

Relevance

Groundwater is a key part of Otago’s water system, sustaining communities, ecosystems, and economic activity across the region. Households rely on groundwater for drinking water, and it supports irrigation, food production, and other land-based industries.

Groundwater also plays an important role in maintaining the flows of rivers, lakes, and wetlands, particularly during dry periods. This helps sustain habitats for native species and supports mahika kai (food and resource gathering). Pathogens, nitrogen, and other contaminants can affect the suitability of groundwater for various uses and can also affect water quality in spring-fed streams and lakes.

For mana whenua, groundwater is an integral part of the wider wai system, connected to surface water, ecosystems, and people. Clean groundwater is part of the exercise of kaitiakitaka (guardianship), supports the practice of mahika kai, and maintains genealogical relationships with water and the wellbeing of current and future generations.

Sustainably managing groundwater requires an integrated approach, recognising that what happens on the land affects both the quality and quantity of water stored underground, and that aquifers are often closely connected to surface waterways.

Current situation

Summary

In most places in Otago, groundwater quality generally meets Drinking Water Standards, except in some parts of North Otago, Taieri, and Ettrick.

Supporting information

In most places in Otago, groundwater quality generally meets Drinking Water Standards, except in some parts of North Otago, Taieri, and Ettrick. While attributing causes to trends is difficult, these patterns are consistent with national trends indicating land use intensification.

Arsenic levels are naturally elevated in schist-dominated areas such as the Upper Lakes Rohe.

How is it measured

For the purpose of this indicator, several measurements have been used to assess the quality of groundwater in Otago’s aquifers:

- Nitrate nitrogen: A measure of contamination that can affect human health and the environment. Expected level for minimally disturbed or natural Otago groundwater is 1 mg/L. Assessment method: median nitrogen concentration over the past five years.

- Escherichia coli (E. coli): A measure of faecal contamination and the presence of pathogens that can pose health risks if ingested. Expected level in minimally disturbed or natural Otago groundwater is no detection (<1 MPN/100 mL). Assessment method: percentage of samples with detections over the past five years.

- Arsenic: A naturally occurring trace metal that can affect human health. Assessment method: maximum arsenic concentration detected over the past five years.

All three of these measurements are assessed against:

- Natural or minimally disturbed groundwater conditions expected in Otago; and

- Drinking Water Standards for New Zealand (DWSNZ) maximum acceptable values (MAVs).

These comparisons help determine whether groundwater is safe for drinking and whether aquifers are moving away from natural conditions, potentially signalling emerging risk.

Relevance

Groundwater is a critical part of Otago’s freshwater system. It supplies drinking water for many rural and urban communities, supports irrigation and land-based industries, and sustains rivers, springs, wetlands, and lakes—particularly during dry periods. Reliable groundwater availability underpins ecosystem health, community wellbeing, economic activity, and resilience to drought and climate variability.

For mana whenua, groundwater is an integral part of the wider wai system, connected to surface water, ecosystems, and people. Maintaining sufficient groundwater quantity is part of the exercise of kaitiakitaka (guardianship), supports the practice of mahika kai (food and resource gathering), and maintains genealogical relationships with water and the wellbeing of current and future generations.

Groundwater quantity also plays an important role in buffering the impacts of drought and increasingly variable rainfall. Aquifers act as natural stores of water, helping to moderate extremes between wet and dry periods. Where groundwater levels decline too far, there is increased risk to connected rivers, wetlands, and water users.

Managing groundwater quantity requires an integrated approach, recognising the close connections between surface water, groundwater recharge, and water demand.

Current situation

Summary

Groundwater quantity is generally good across Otago, but some areas are vulnerable during seasonal dry periods and dry years.

Supporting information

Across most of Otago, groundwater levels are stable, and groundwater quantity is not a limiting factor for ecosystems or people.

In a small number of aquifers, groundwater levels are declining. These declines are not currently considered a significant risk to water availability or ecosystem health. In several cases, the declines reflect changes in irrigation practices—particularly the shift from flood irrigation to more efficient spray and pivot systems.

Under flood irrigation, large volumes of water historically recharged shallow aquifers. As irrigation efficiency has improved, this artificial recharge has reduced, resulting in lower but more natural groundwater levels. At present, there is no widespread evidence of groundwater over-allocation or region-wide depletion.

Some aquifers have less water available during dry seasons or dry years, these aquifers recover quickly when the dry period ends. These patterns are less visible in long term trends, but are important management considerations with increasingly regular drought and extreme weather.

How is it measured

Groundwater quantity is monitored through a network of long-term observation bores across Otago that measure groundwater levels over time. These records show how aquifers respond to rainfall, recharge, seasonal demand, and longer-term land-use change.

Groundwater level trends are assessed alongside information on water takes, recharge conditions, and known connections to surface water. This information is used to understand whether groundwater levels are stable, rising, or declining, and whether observed changes present risks to ecosystems or water users.

Relevance

Otago’s lakes are central to the region’s identity, supporting biodiversity, recreation, community wellbeing, and the economy. Healthy lakes provide habitats for indigenous plants and wildlife, contribute to the resilience of connected rivers and wetlands, and support recreational activities such as swimming, boating, fishing, and camping.

Many of Otago’s lakes are nationally significant for recreation and tourism, underpinning local economies in places such as Queenstown and Wānaka. Good water quality is vital to ensure lakes remain safe for swimming, accessible for recreation, and attractive to visitors. Once lake water quality declines, it is often very difficult to reverse.

Lakes also provide long-term storage of freshwater and help moderate flood peaks and drought effects, making them important for resilience to drought and increasingly extreme weather.

Mana whenua hold deep ancestral relationships with the lakes of Otago, many of which are embedded in creation traditions and sustained generations through mahika kai (food and resource gathering), travel routes, and settlement sites. Today, mana whenua continue to exercise their role as kaitiaki (guardians) of healthy lakes and waterways.

Managing lake water quality requires recognising the connections between land use, inflowing rivers and streams, groundwater, and surrounding ecosystems. Activities such as urban development, farming, and forestry can affect nutrient levels, sediment, and clarity, influencing lake health over time. Integrated management is necessary to ensure lakes, their catchments, and downstream rivers are managed as connected and interdependent systems.

Current situation

Summary

Shallow lowland lakes in Otago tend to have poor and declining water quality. High-country deep lakes currently have very good water quality, but there are early signs of reduced resilience.

Supporting information

Shallow lowland lakes, located at the bottom of their catchments, generally have poorer and declining water quality. In contrast, Otago’s high-country deep lakes currently have very good water quality, but are showing emerging signs of change, including bioinvasion and rising chlorophyll-a (algae) levels.

While attributing causes to trends is difficult, these patterns are consistent with national trends associated with land use intensification.

Algae (chlorophyll-a) levels appear to be increasing in all 8 monitored lakes Water clarity is also deteriorating at many sites. Nitrogen levels are deteriorating in most of the 8 lakes , but phosphorous levels are improving.

E. coli levels are improving in Lake Dunstan, but deteriorating in Lake Whakatipu. These short-term trends are likely to be strongly influenced by recent hot, dry climatic conditions.

How is it measured

Otago has more than 80 named lakes, but only a small number have long-term, consistent environmental monitoring. For this indicator, the focus is on eight lakes with reliable trend data collected through ORC’s State of the Environment monitoring programme: Lakes Wānaka, Whakatipu, Hāwea, Hayes, Dunstan, Onslow, Waihola, and Tuakitoto.

This is the only multi-year dataset for lake water quality in Otago, allowing changes to be assessed over time.

For the purpose of this indicator, several measurements were used to assess whether water quality in these eight lakes improved or deteriorated between 2017 and 2022, including:

- Trophic Level Index: A measure of overall lake condition combining chlorophyll-a, total phosphorus, total nitrogen, and water clarity (Secchi disc depth).

- Chlorophyll-a: A measure of the amount of phytoplankton (algae) in the water. High levels can degrade water quality and aquatic ecosystems.

- Total phosphorus and total nitrogen: Nutrients that can lead to elevated plant and algal growth.

- Clarity: A measure of how clear the water is and how much light is available to aquatic life.

- Ammonia toxicity: A nutrient that can harm fish and other aquatic life at high levels.

- Escherichia coli (E. coli): indicating faecal contamination and the presence of harmful pathogens that may cause illness.and human health risk.

Relevance

Wetlands are among Otago’s most important and multifunctional ecosystems. They filter and store water, trap sediment and nutrients, store carbon, moderate floods, and support a high diversity of indigenous plants and animals.

Healthy wetlands help maintain the resilience of rivers, lakes, groundwater, and coastal environments by slowing water movement, improving water quality, and sustaining flows during dry periods. As rainfall patterns become more variable and extreme weather events more frequent, wetlands provide natural buffering against floods and droughts, helping protect downstream communities, infrastructure, and ecosystems.

For these reasons, both natural and constructed wetlands are increasingly recognised as integral components of land use across cities, towns, and farm systems. Maintaining wetland extent and condition is essential for ecological integrity, economic wellbeing, cultural values, and regional resilience.

Mana whenua hold deep ancestral relationships with the wetlands of Otago, which were once among the region’s most important mahika kai (food and resource gathering) landscapes. Wetlands sustained generations through food gathering, seasonal occupation, and extensive networks of trails and settlements.

Wetlands such as Waihola–Waipori, Tuakitoto, and wider coastal and inland wetland systems supported abundant food resources and cultural practices that continue to hold significance today.

What happens upstream directly affects what happens downstream. Managing wetlands requires an integrated approach that recognises connections between wetlands, streams and rivers, groundwater, and coastal environments.

Effective management also depends on understanding where wetlands are located, their extent, and their type, so pragmatic and proportionate approaches can be taken to protect wetlands and the wide range of benefits they provide.

Current situation

Summary

Despite historic loss and ongoing pressure, Otago still has more than 10,000 hectares of mapped wetlands.

Supporting information

Despite approximately 76% of Otago’s wetlands having been drained or developed for agriculture or urban use, the region still contains more than 16,000 hectares of mapped wetlands, with around 62% of the region completed to date.

Nationally, around 90% of Aotearoa New Zealand’s wetlands have already been lost, meaning Otago now holds a disproportionately important share of what remains.

These wetlands retain high ecological, cultural, economic, and social value. However, site-specific studies and early monitoring show they are under increasing pressure from invasive species, vegetation and soil damage, drainage, and nutrient runoff.

The current monitoring programme has also revealed that wetlands are more numerous and more widely distributed than previously understood, with more than 25,000 additional wetlands identified so far.

How is it measured

Wetland health in Otago is assessed through two key aspects: extent (how much wetland remains) and condition (how well wetlands are functioning).

Wetland extent is measured using high-resolution aerial imagery, satellite data, national datasets, and field verification. This work identifies where wetlands are located, their size, and their broad type. Mapping is being progressively completed across Otago, providing a baseline for tracking future loss, protection, or restoration over time.

Wetland condition is assessed through field-based surveys that examine attributes influencing wetland function. These include hydrology, vegetation composition and structure, soil condition, and pressures such as drainage, invasive species, stock access, earthworks, and nutrient or sediment inputs.

Monitoring is designed to represent the diversity of wetland types, land uses, and landscapes across the region. This monitoring programme has only recently commenced and will provide an understanding of the state of Otago’s wetlands. Trends will become apparent as repeat monitoring cycles are completed.

Relevance

Otago’s indigenous biodiversity includes the plants, animals, fungi, and ecosystems that occur here naturally, along with their habitats and the relationships between them. Otago communities value indigenous biodiversity for its own sake, as part of our regional identity and tourism brand, and as a foundation of the natural systems that provide clean water, fertile soil, climate regulation, and protection from floods and erosion.

For mana whenua, indigenous species and habitats are taoka (treasures) that are connected to people and place through whakapapa (genealogical relationships). Caring for these species and ecosystems is a core part of kaitiakitaka (guardianship), and the condition of taoka species often signals how well the environment is functioning.

Protecting and restoring indigenous biodiversity also supports cultural practices such as mahika kai (food and resource gathering) and helps uphold responsibilities to future generations.

ORC has a key role in maintaining indigenous biodiversity in Otago. This includes understanding the state of indigenous biodiversity to determine whether it is improving or declining, why it is in its current state, and what actions and methods can help maintain it.

This information is used to inform the Regional Policy Statement, water and coast plans, and practical actions such as supporting and empowering mana whenua, community groups, landowners, and businesses.

Current situation

Summary

Otago’s indigenous species and ecosystems are declining.

Supporting information

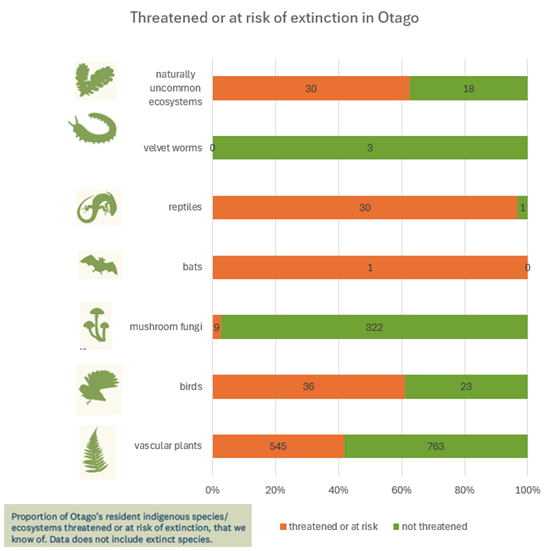

A high proportion of indigenous species and ecosystems in Otago are threatened or at risk of extinction within the next ten years.

- 42% (545 of 1,315) of vascular plants

- 61% (36 of 59) of birds

- 97% (30 of 31) of reptiles

- 100% (1 of 1) of bats

- 3% (9 of 331) of mushroom fungi

These figures relate to resident indigenous species in Otago and do not include species that are already extinct.

How is it measured

The risk of extinction measures how likely a species or ecosystem is to be lost within ten years or three generations. This is a central part of maintaining indigenous biodiversity.

Nationally, extinction risk is measured using the New Zealand Threat Classification System (NZTCS). In Otago, this is assessed using the Regional Threat Classification System, which complements the NZTCS and provides information that is more relevant to ORC’s regional role.

The regional threat classification indicates whether biodiversity is being maintained in Otago and can also be used as a measure of how successful efforts to protect species and ecosystems have been. The trends presented here are based on the first set of regional threat assessments.

Relevance

Clean air is essential for the health and wellbeing of Otago’s communities. Good air quality supports daily life by helping people breathe easily, enjoy outdoor activities, and reduce the risk of respiratory and cardiovascular illness. Air quality also influences the liveability of towns, the experience of visitors, and the overall identity of the region.

For mana whenua, air is part of the wider natural system whose mauri must be protected. Relationships with the environment include responsibility for safeguarding the health of taoka and the conditions that sustain them, which extends to the quality of air that influences human and ecosystem wellbeing. Clean, healthy air supports kaitiakitaka, cultural practices, and intergenerational wellbeing.

Otago Regional Council plays a key role in managing and improving air quality across the region. ORC monitors air pollutants and weather conditions to understand when and where air quality issues occur, and how they are changing over time.

This monitoring informs the Regional Plan: Air, supporting consent decisions, the management of discharges, and regional and local action to reduce pollution. ORC works with communities, public health agencies, local councils, and homeowners to encourage cleaner heating choices and reduce emissions at the source.

By improving air quality, ORC helps protect the health of families and communities, supports vibrant and liveable towns, and supports progress towards meeting national air quality standards.

Current situation

Summary

While several towns still regularly exceed national standards in winter, air quality in six of the seven monitored towns is improving very slowly. Air quality in Alexandra is not improving.

Supporting information

Most of Otago enjoys good air quality for much of the year. However, during winter, Alexandra, Arrowtown, Clyde, Cromwell, Milton, and Mosgiel experience high levels of fine PM10 particles.

This pollution results primarily from seasonal sources such as home heating, combined with cold, still weather conditions that trap smoke close to the ground. Fine particles can enter the lungs and bloodstream, posing health risks, particularly for older people, children, and those with respiratory conditions.

During winter, these towns regularly exceed the National Environmental Standard for Air Quality (NESAQ) for PM10. Outside winter, concentrations are generally low and meet the annual Ambient Air Quality Guideline (AAQG).

Long-term trend analysis indicates that PM10 concentrations have improved in Arrowtown, Central Dunedin, Clyde, Cromwell, Milton, and to a lesser extent, Mosgiel. In Alexandra, analysis indicates air quality is not improving, although further data are required to confirm this.

How Otago’s towns are tracking (2005–2023)

Air quality has improved in six of the seven monitored towns, largely due to cleaner home-heating systems, improved fuel choices, and targeted community support. Alexandra remains the only town where air quality is not improving.

How is it measured

Otago’s air quality is monitored through a network of long-term monitoring stations that continuously measure particulate matter (PM10) in towns that experience the poorest air quality in the region.

Frequency

Continuous and seasonal monitoring has been occurring since 2005. Data are analysed to determine current state and long-term trends every five years.

Relevance

Estuaries are important to Otago communities, providing a strong sense of place and a wide range of recreational opportunities while supporting food gathering, buffering storm impacts, recycling nutrients, and storing significant amounts of carbon.

These ecosystems contain exceptionally high biodiversity, with thousands of plant and animal species, and support key stages of the life cycle for both freshwater and marine species. They support commercial fisheries, mahika kai, and recreational fishing. Estuaries also serve as important nursery areas (kōhaka) and are home to waterfowl, shellfish, freshwater crayfish, eels, lamprey, whitebait, other fish species, and a variety of plant resources.

Large flocks of migratory wading birds depend on Otago’s estuaries for feeding and resting, linking these places to global ecological networks.

The coastal environment has been integral to mana whenua ways of life for generations. Estuaries were traditionally important for settlement and travel and continue to provide for communities through mahika kai. Kaimoana (seafood) is essential to coastal mana whenua relationships with the environment and is an important indicator of the health of coastal ecosystems.

Current situation

Otago’s estuaries have historically lost a large proportion of saltmarsh. Many currently have muddiness levels that reduce ecosystem function, and a number of intermittently closed estuaries are at higher risk of eutrophication.

Supporting information

Saltmarshes: There has been an estimated 61% loss of saltmarsh across the Otago region, reflecting long-term historical change.

Open estuaries: Eight of the eleven monitored estuaries in Otago have muddiness levels exceeding the 25% threshold known to negatively affect biodiversity, ecosystem function, and overall estuary resilience. Three estuaries — Blueskin Bay, Pūrākaunui Inlet, and Waipati/Chaslands — have low mud content across their broader areas.

Most monitored sites (10 of 11 estuaries) show sedimentation rates above the national guideline of 2 mm per year. This is likely influenced in part by the October 2024 flooding combined with catchment activities. Ongoing sedimentation and increasing muddiness remain important trends to monitor.

Intermittently closed estuaries (ICEs): Otago has 44 intermittently closed estuaries. Early assessment based on available data indicates that 16 of these are at higher risk of eutrophication.

[Map]

How is it measured

For the purpose of this indicator, the health of different kinds of estuaries is measured in different ways:

Saltmarshes. Saltmarsh extent is part of estuary health because saltmarshes support biodiversity, help stabilise shorelines, filter nutrients and sediment, store significant amounts of carbon, and provide resilience to severe weather and sea level rise.

Open estuaries. Muddiness (the accumulation of fine sediments on intertidal flats) is a key measure of estuary health in estuaries that are open to the ocean. A small amount of mud can be beneficial because it can contain organic matter that some animals feed on, and estuary ecosystems are most resilient when mud content is less than 10 per cent. When mud content is between 10 and 25 per cent, there is a noticeable decline in ecosystem function and resilience. When mud content exceeds 25 per cent, estuary communities become unbalanced. Once mud content is over 60 per cent, the ecosystem is degraded.

Intermittently closed estuaries (ICEs). Chlorophyll a (a measure of algal biomass), together with nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations, are used as measurements of health for estuaries that are sometimes closed to the ocean. When these estuaries close, water becomes trapped, allowing nutrients and algae to build up quickly. At a certain point, this build-up becomes so high that the estuary can become eutrophic, causing low oxygen levels, blocked light, strong smells, fish kills, and temporary ecosystem collapse. Because muddiness in this type of estuary can change significantly and is often reset when the estuary reopens to the ocean, it is a less reliable measure of overall health.

Monitoring of both open estuaries and intermittently closed estuaries (ICEs) is at an early stage. Only five estuaries have sufficient data (five years or more) to begin assessing trends, and none have the recommended 10-year timeframe for robust trend analysis. The measure for ICEs is based on historical data and targeted sampling, rather than a consistent long-term programme.

As the interface between land, freshwater, and the sea, integrated management of the environment is key to estuary health. What happens upstream affects downstream environments.

Relevance

Otago’s near-shore marine environment supports a wide range of ecological, cultural, social, and economic values. Rocky reefs, kelp forests, sandy seabeds, and coastal waters provide habitat for indigenous marine species, support commercial and recreational fisheries, and contribute to the region’s identity, recreation, and tourism economy.

Healthy near-shore ecosystems play a critical role in buffering the coast from wave energy and erosion, cycling nutrients, and supporting food webs from plankton to top predators. Kelp forests, in particular, are foundation ecosystems that enhance biodiversity, stabilise sediments, and provide refuge and feeding areas for many species.

The coastal environment has been integral to mana whenua ways of life for generations. It was traditionally important for settlement and travel and continues to support settlement and mahika kai. Kaimoana (seafood) is essential to coastal mana whenua relationships with the environment and is an important indicator of coastal health.

Near-shore marine health is strongly influenced by activities on land. What happens in catchments and freshwater ecosystems directly affects coastal and marine habitats. Warming seas and ocean acidification are increasing ecosystem vulnerability, making good coastal water quality critical for maintaining resilience.

Integrated environmental management is key to protecting and improving coastal water quality.

Current situation

Summary

In some parts of Otago, coastal water quality is declining, reducing the resilience of key marine ecosystems such as kelp forests in the face of rising ocean temperatures and ocean acidification.

Supporting information

Coastal water quality is declining in some parts of Otago. Increased sediment and nutrient inputs are reducing water clarity and altering near-shore conditions, particularly following high-rainfall and flood events. These pressures reduce light availability and increase stress on sensitive marine habitats.

Kelp forests and other near-shore ecosystems are showing reduced resilience to climate-related stressors. Warmer sea temperatures and ocean acidification place additional pressure on marine species, and where water quality is degraded, ecosystems are less able to recover.

While impacts are not uniform along the coast, the overall pattern indicates growing cumulative pressure on near-shore marine ecosystems. These trends highlight the importance of managing sediment and nutrient inputs from land.

[Map]

How is it measured

For the purpose of this indicator, coastal and marine health is assessed using a combination of coastal water quality data, ecological monitoring, and targeted research programmes.

This includes measures of:

- Coastal water quality

- Sea surface temperature

- Chlorophyll-a (as a proxy for phytoplankton productivity)

- Sediment loading

- Acidity (pH)

- Ecosystem extent

- Kelp / Macrocystis coverage, reflecting the condition and extent of key coastal habitats that support biodiversity and ecosystem functioning

This indicator uses the best available evidence to describe current state and emerging trends. As monitoring networks and research programmes expand, the precision and resolution of coastal health assessments are expected to improve.

Relevance

Healthy soils are fundamental to life in Otago. They support food production systems, filter and store water, cycle nutrients, and provide the foundation for thriving ecosystems, farms, forests, and communities.

Good soil health helps maintain landscape stability by reducing erosion, protecting waterways from sediment and nutrient loss, and supporting the resilience of both rural and urban environments.

For mana whenua, soils form part of the wider natural system whose mauri must be protected. Healthy, functioning soils support mahika kai species and habitats and are essential for exercising kaitiakitaka (guardianship) and upholding intergenerational responsibilities.

Soils contribute directly to Otago’s economy by supporting agriculture, horticulture, viticulture, and forestry, and they underpin the region’s identity. Healthy soils help buffer the effects of droughts, intense rainfall, and climate change by absorbing and storing water, supporting vegetation cover, and maintaining productive landscapes.

When soils become compacted, eroded, or depleted, the impacts are felt widely — including reduced productivity, poorer water quality, increased sediment in rivers and lakes, loss of biodiversity, and reduced resilience to extreme weather events.

ORC sets regional policy and planning rules to manage land use, prevent soil degradation, and reduce the loss of sediment and nutrients into waterways. ORC works with landowners, industry groups, mana whenua, and local councils to promote good land-management practices, prevent erosion, and support sustainable farming and horticulture.

ORC also monitors soil quality at representative sites across Otago to understand how soils are performing, how land-use pressures are changing, and whether soil health is improving or declining over time.

Current situation

Summary

Soil health in Otago is generally good across the majority of monitored sites. However, in some land uses, soil compaction and nutrient depletion or oversupply are emerging issues.

Supporting information

Early results indicate that soil health is generally good across most monitored sites, but some pressures are emerging.

Around a quarter of sites show signs of soil compaction, which reduces the movement of water, air, and roots through the soil.

At a number of sites, key nutrients and soil organic matter are lower than ideal, indicating gradual depletion of carbon and nutrient reserves that help soils store water, support plant growth, and maintain resilience to drought.

At other sites, some nutrients are elevated above recommended levels, increasing the risk of nutrient loss to waterways.

While these issues are not universal and occur across a range of land uses, the majority of monitored sites still fall within adequate ranges. This suggests that many land-management practices in Otago are working well.

As the monitoring network continues to expand, ORC will begin resampling in 2027, enabling clearer reporting of long-term trends in soil health.

How is it measured

ORC monitors soil health through a region-wide network of long-term monitoring sites representing the range of land uses, soil types, and landscapes across Otago.

Each site is sampled every five years to track changes in soil compaction, organic matter, nutrient balance, and soil structure over time. Trace metals and other contaminants relevant to human and environmental health are also monitored.

Long-term soil health trends will be apparent once repeat sampling begins in 2027.